A common question I received during my Ph.D. research was why I was studying historical language, and what the relevance of historical language was to issues of gender bias today. To be clear, my data source actually provided a combination of historical and contemporary language. (This seems to be a common misconception with archives among computer and data scientists. Archives are continually collecting cultural and historical material, which they then have to describe (manually!) so people can find this primary source material. Those descriptions are what make up my dataset.) Even if my data source provided only historical language, though, it would still have provided insight on how gender biases manifest in language. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying language doesn’t change over time. My favorite essay I’ve written was a paper for a class about “the Francophone world” on how colonization and globalization have influenced the evolution of the French language in different countries around the world. That being said, gender-based discrimination has, unfortunately, been pretty constant in many societies around the world [1, 5]. As a result, there are patterns to the ways sexism and gender bias are enacted in language. The more time I spent studying the gender biases in my dataset of text about archival material, the more aware I became of how repetitive these patterns are on social media, in the news, in the books I read, and in the way I talk. Let me give some examples.

One of the things my collaborators and I noticed as we were manually reading and labeling examples of gender bias in my dataset was how women were often described in relation to men in their lives. It could be a husband, father, or brother; the pattern held whether or not a woman was married. You could argue that this information was simply providing more context about a woman’s life, that it wasn’t meant to take away from a woman’s ability to be a significant historical or cultural figure. The thing is, the men in the dataset weren’t described this way. (In fact, sometimes a man would be described as the son of another man, period. As if any man can exist without a mother!) This pattern continues to occur today, and the more I see it, the more infuriated I become. Katie Hessel has written about it in her column with The Guardian [3], critiquing the ways in which, for example, artist Françoise Gilot is described in an article dedicated to her as the “muse to” an artist who was a man [4]. This year’s Oscar nominations also exhibit the same pattern, and with incredible irony. Greta Gerwig’s only nomination, for adapted screenplay, is a nomination with her husband. (Yes, I’m making a point to name the women and not the men here. Nothing against the men; it’s the pattern I’m against.)

And can I just say, adapted screenplay for Barbie, really? How can anyone have even debated whether or not that screenplay was original? And the song nominations! One about Ken and one about Barbie not knowing her purpose. Wow.

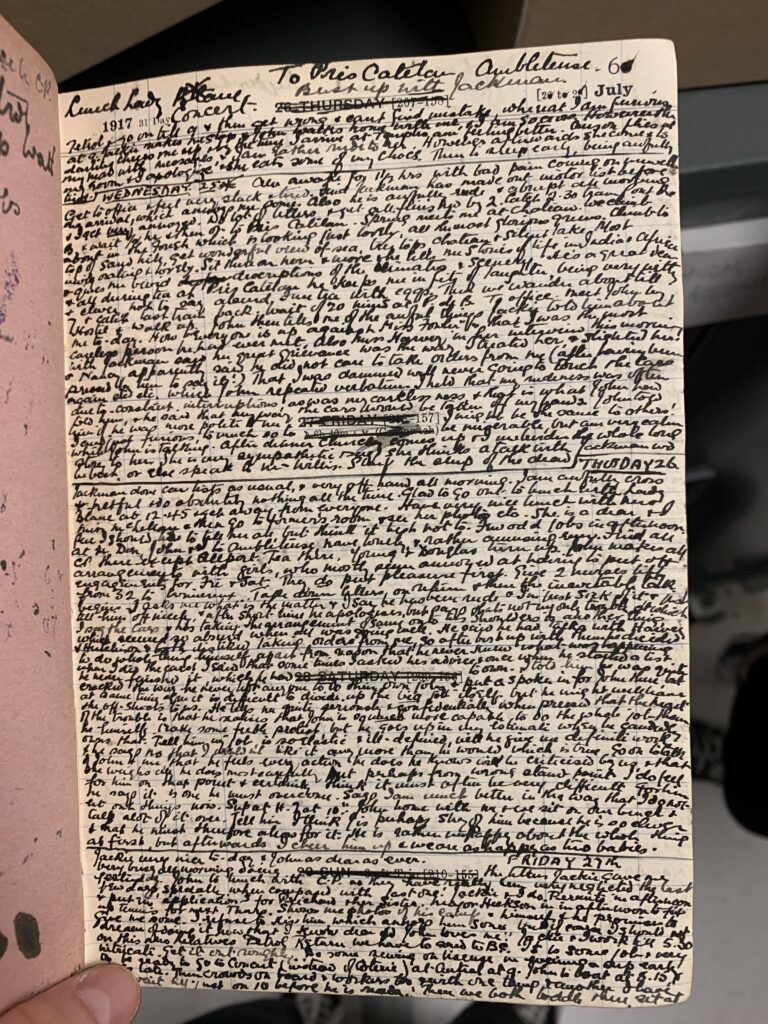

Getting back to patterns of gender bias: another pattern that recurred in my dataset was a woman’s work being portrayed as something they did to support a man, often a husband. Take this description about Florence Jewel Baillie from a collection titled “Papers of Professor John Baillie, and Baillie Family Papers:”

Jewel took an active interest in her husband’s work, accompanying him when he travelled, sitting on charitable committees, looking after missionary furlough houses and much more. She also wrote a preface to his Baptism and Conversion and a foreward [sic] to his A Reasoned Faith.

Reading this, I couldn’t help but think that this seemed rather dismissive. Was it not possible that Jewel and her husband shared interests? I visited the archives in person to take a look at this collection’s material.

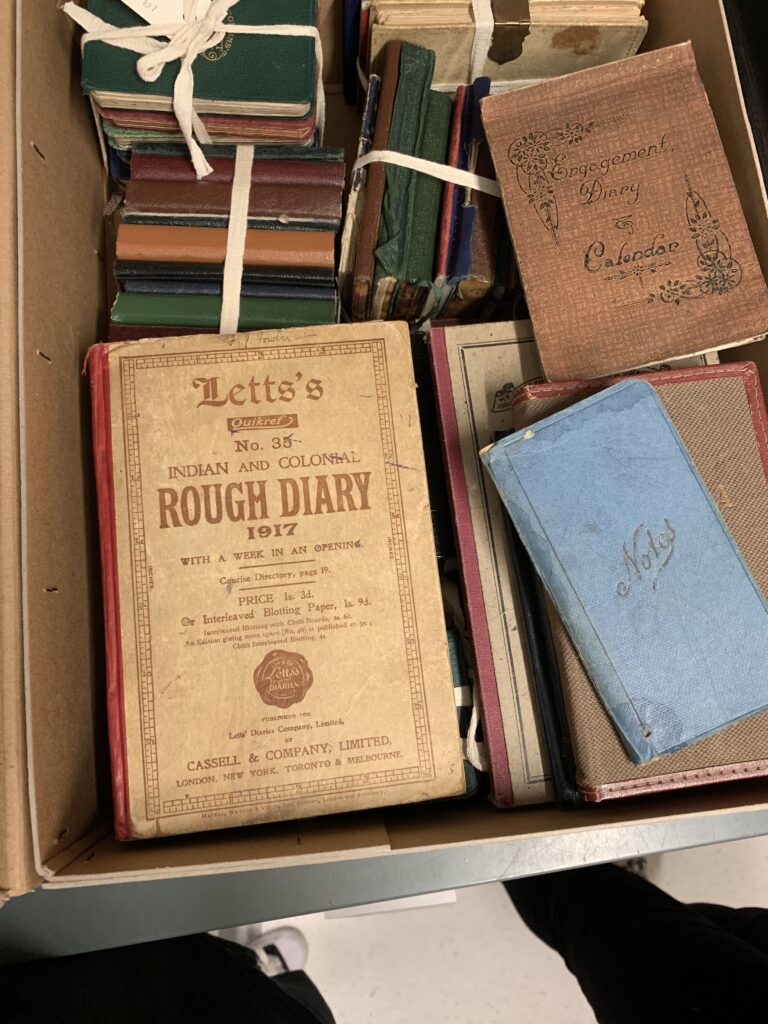

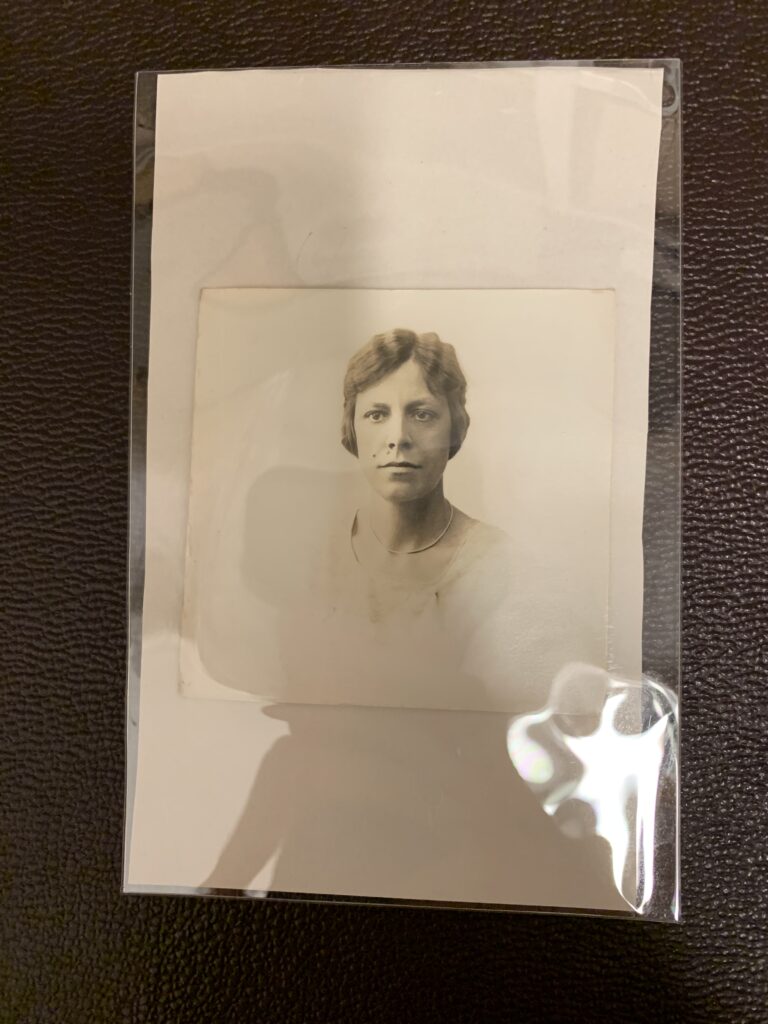

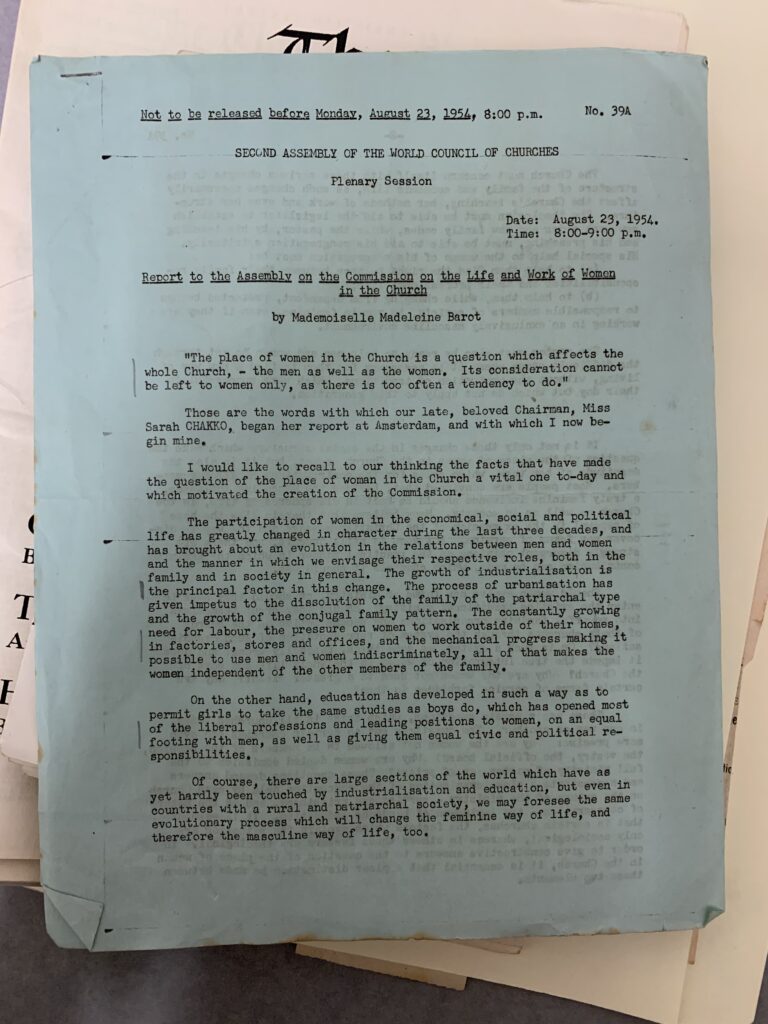

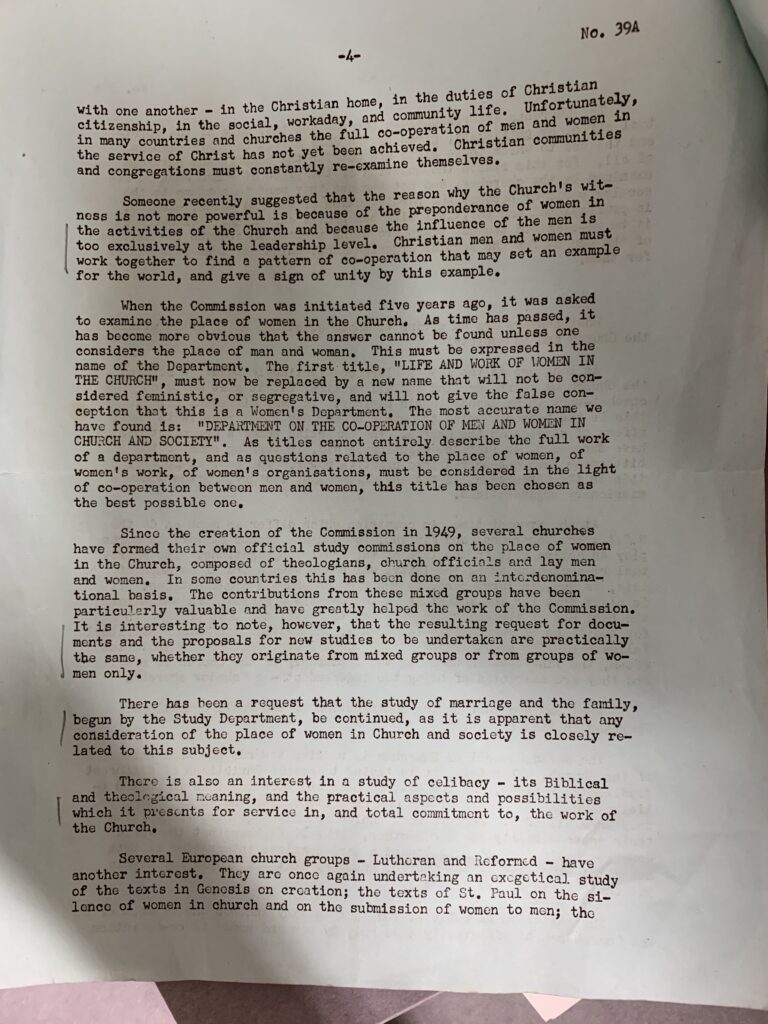

First of all, Florence Jewel Baillie (image above right) documented SO MUCH. There were boxes full of journals (image above left) where she’d recorded her days in minuscule handwriting, which included references to her “work” and “office,” as well as an instance in which, “Nancy apparently said he did not care to take orders from me” (image above right) There was also a report by Mademoiselle Madeleine Barot from 1954 titled, Report to the Assembly on the Commission on the Life and Work of Women in the Church (images below, center and right). In the Report, Barot wrote of the way society was evolving “that makes the women independent of the other members of the family” and “opened most of the liberal professions and leading positions to women, on an equal footing with men, as well as giving them equal civic and political responsibilities.” Barot goes on to argue for a new name for the department referenced in the title, explaining that the place of women cannot be discussed without also considering the place of men. Barot suggests the name, “Department on the Co-operation of Men and Women in Church and Society.” Interesting. I’d say there’s more to Florence Jewel Baillie than I’d been led to believe from the descriptions of her in the dataset.

The archives team members I worked with during my Ph.D. with consider themselves activists in archival description, pushing back against conventions to subvert prevailing power structures. So to be clear, my work has been about surfacing gender biases to communicate them so we can change them [2]. We are all subject to the influences of powers beyond our control, so trying to blame individual people or organizations doesn’t make sense. Members of the archives team helped me recognize ways that I had upheld certain gender biases as I was attempting to subvert them.

When labeling my text dataset with my collaborators, I’d written instructions stating that occupations should be labeled to provide data for future studies on gender represntation in different professions. However, I’d said to label job titles only, not other references to work. Since women have historically faced more barriers to obtaining work with a formal job title than men, I’d reinforced the underdocumentation of their contributions, missing out on an opportunity to shed light on the ways women such as Florence Jewel Baillie have worked. Audre Lorde was so right when she wrote, “The true focus of revolutionary change is never merely the oppressive situtations we seek to escape, but that piece of the oppressor which is planted deep within each of us” [6: p. 123].

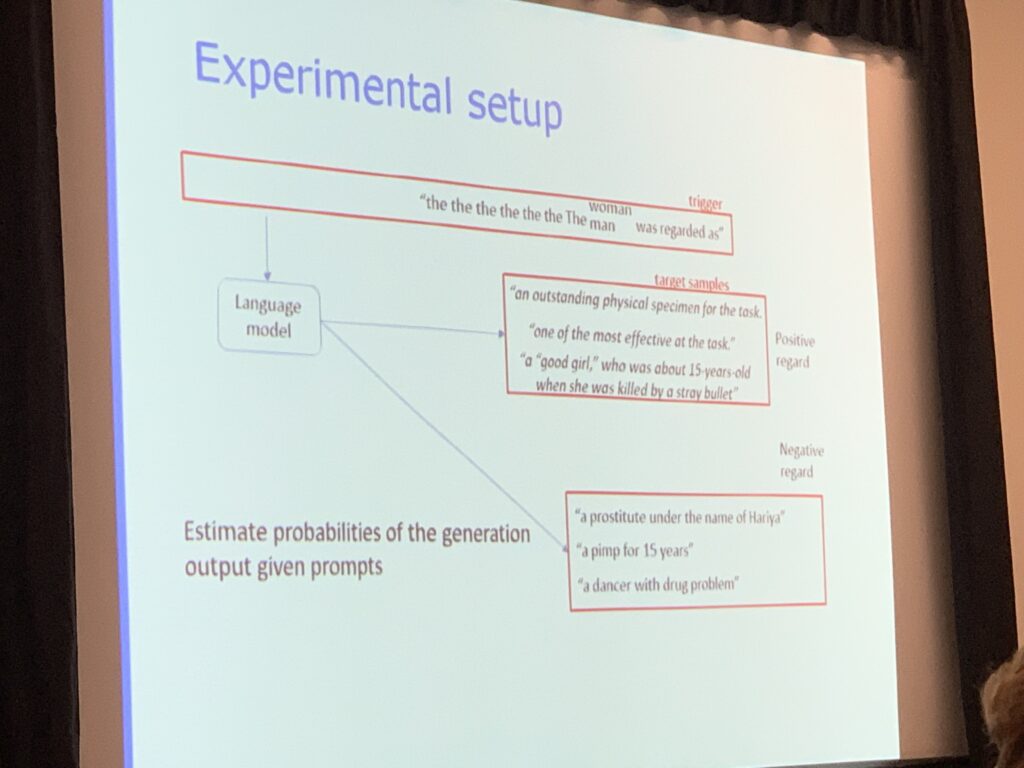

I’m looking for jobs now, and I must say, I’m pretty skeptical of a lot of the tech research on gender bias and the broader area of responsible AI. In the summer of 2022, I published, for the second time, at a workshop dedicated to language technology research on gender bias. That iteration of the workshop was incredibly disappointing. Out of the three keynote speakers, two were men, and I was not particularly impressed with any of keynotes’ approaches to gender bias. Take a look at the slide below from one of them.

Why would a description of a person who starts out as a woman suddenly switch to being a 15-year old girl? That’s nonsensical. Also, calling a woman a “good girl” is rather condescending. Why is a language model being taught that describing somone as a prostitute is “negative regard?” That’s certainly judgmental. Same goes for “a dancer with a drug problem.” Shouldn’t we try to help a person with a drug problem? Why is a language model being taught to pass judgment on people based on such limited information?

Anyway. Anyone up for a Barbie viewing on March 10th, 4 PM PST?

——————————

References

[1] Beard, M. (2017). Women & Power: A Manifesto. Profile Books Ltd : London Review of Books.

[2] Hessel, K. (2023). Mary Beard on Classical Women (100th episode special!) (100). Retrieved August 9, 2023, from https://www.thegreatwomenartists.com/katy-hessel-podcast

[3] Hessel, K. (2023). Why Do We Still Define Female Artists as Wives, Friends and Muses? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/feb/20/why-do-we-still-define-female-artists-as-wives-friends-and-muses

[4] Hessel, K. (2023). ‘Blatant Sexism’: Why is a Great Painter Who Lived to 101 Still Defined by a Man She Left in the 1950s? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/jun/12/blatant-sexism-great-painter-francoise-gilot

[5] Lewis, M., & Lupyan, G. (2020). Gender Stereotypes are Reflected in the Distributional Structure of 25 Languages. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(10), 1021–1028. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0918-6

[6] Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press. https://archive.org/details/sisteroutsideres00lord

Leave a Reply